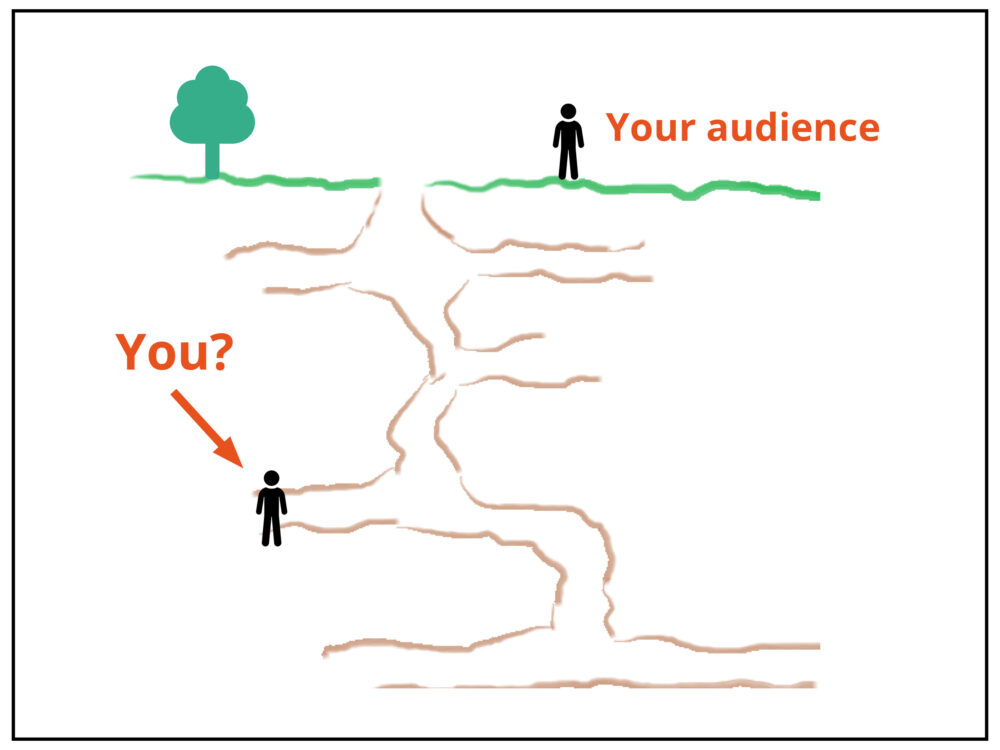

How deep down are you?

The longer you do research or perform any other type of work, the deeper you dig. This is called expertise. You begin with both of your feet on the ground. During your Bachelor or Master studies you start digging a first hole. This is followed by a doctorate and perhaps even a postdoctoral study. You continue digging deeper toward greater knowledge, becoming all the more of an expert.

At a certain moment, you look up. And what do you see? You are no longer in an ivory tower, but instead find yourself amid a complex tunnel system. Although the general public is still at the surface above, they have no idea that you are still around and couldn’t even begin to understand you.

Meanwhile, you are preoccupied with specific proteins, mathematical structures or advanced psychological models. Your audience may have a vague understanding of what DNA is, even know what a derivative is, or who Sigmund Freud was.

But how will you share your research with those people at the surface? Certainly not by blindly pushing them into your complex tunnel system and merely hoping they will make it out alive. That is what most researchers would do, … but surely you are much smarter than that.

Start with what they know

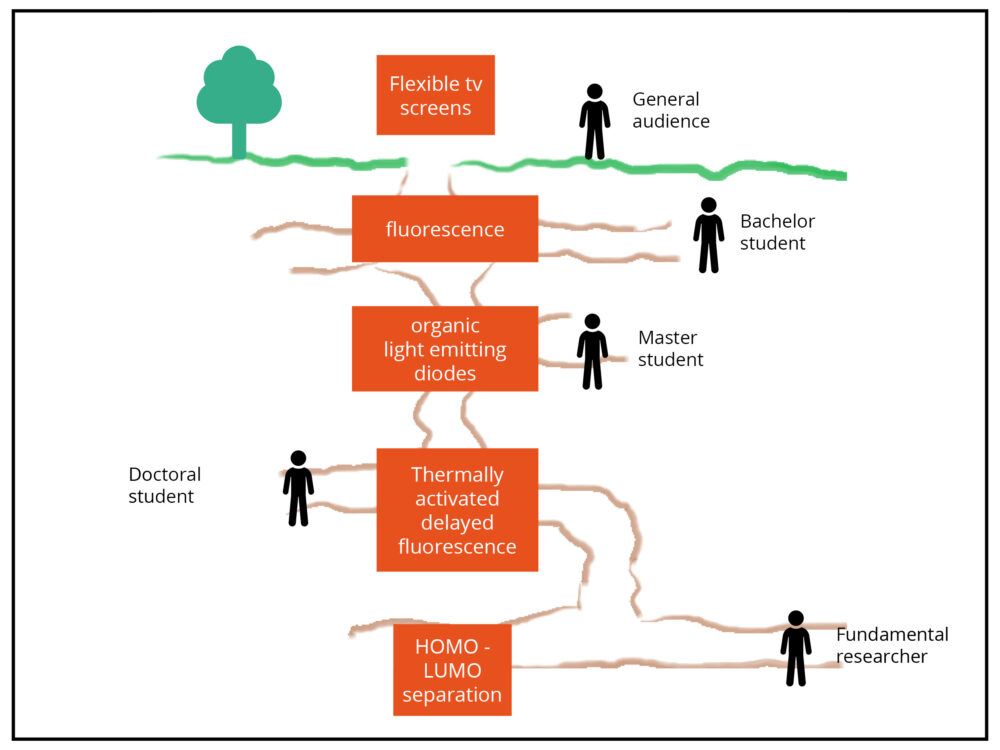

Just recently, I was talking with a researcher who worked on ‘thermally activated delayed fluorescence’. I had never heard of this before. I learned that this technique could one day be used to create flexible tv monitors. Now, that I could understand. So why not begin by mentioning those flexible TV monitors first and then gradually direct me toward your research.

These are some possible steps:

- Flexible TV monitors

- Fluorescence

- Delayed fluorescence

- Organic light-emitting diodes

- Thermally activated delayed fluorescence

Plenty of speakers will introduce their talk with ‘My name is Toon Verlinden and I do research on ‘thermally activated delayed fluorescence’. By doing so, you inadvertently push your audience down the dreaded knowledge hole. You can only hope that they will make it out alive. No wonder your audience will give you the dead fish eyes stare and not understand a single word you are saying. Forget about making an impact.

Always ask yourself: what does my audience already know? Go through this mental exercise for every group you will be speaking to. You could be speaking to experts, but that does not mean you should begin at the deepest level. Those experts could be working in an entirely different tunnel system and using other terminology.

You will not always reach deep enough

There is a problem with this approach. If you are allowed to present for only 15 minutes, you will not always reach the level of your research. That makes sense: if you are first to explain flexible TV monitors, fluorescence and organic light emitting diodes before reaching delayed fluorescence and ‘thermally activated delayed fluorescence’, then 15 minutes will not do the trick.

Accept this and go on.

Sometimes it is enough for your audience to have briefly followed you into your complex cave system and for them to have become aware of your research. You could attempt to explain everything in those 15 short minutes, but that would mean pushing your audience into an abyss and losing them forever by the end of your presentation.

Some scientists participating in the Battle of the Scientists also never get to the topic of their research. Instead, they take pleasure in having been able to show the kids in 15 minutes what a wondrous world is hiding right beneath their feet.

Five levels

Want to know what descending into a tunnel system should look like? Take a look at these videos from Wired magazine, in which an expert explains a concept in five levels of difficulty.

In this video an expert explains the CRISPR technique to a

- Child

- Teenager

- Master student

- PhD student

- CRISPR expert

If the presenter were to fire off the expert explanation at you, you would be utterly lost. But by guiding you along, step-by-step, you will eventually understand the CRISPR expert! (more or less, at least :))

Notice how the researcher does his best to explain CRISPR to a child, but how the boy continues to draw him back to something he understands.

Researcher: (About the genome) ‘There is an instruction manual that makes you who you are, and sometimes there are mistakes in the instruction manual.’

Child: ‘Mistakes, like allergies?’

Researcher: ‘Yes, like allergies’.

This shows that the researcher started at a level that was too low. He should have first mentioned allergies. For instance:

Researcher: ‘Do you sometimes have allergies?’

Child: ‘Yes.’

Researcher: ‘Sometimes there are little mistakes in the instruction manual that make you who you are. And those mistakes can cause allergies.’

When talking to the Master student, the presenter immediately asks him: ‘Do you know how CRISPR works?’ He begins with what his audience knows.

I can also recommend watching the next 5-levels of difficulty video, in which a neuroscientist explains just what a connectome is.

Conclusion: are you preparing a talk? Remember to keep your audience in mind. Ask yourself what level they are at. Start with what they know and guide them along, step by step. And keep your cool when you do not reach the topic of your research. An interested audience is better than a dead one.